Grade Inflation

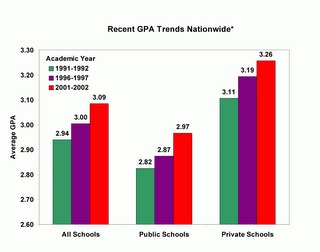

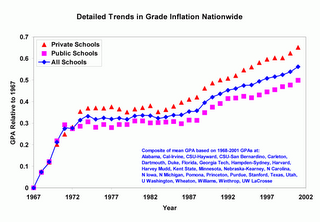

Graphs above are from the website GradeInflation.Com, run by a retired Duke University professor.

Graphs above are from the website GradeInflation.Com, run by a retired Duke University professor.Also, there is an article titled "When Bs Are Better" in the current issue (subscription required) of The Chronicle for Higher Education (subscription required) by a Rutgers management professor:

In the fall of 2001, The Boston Globe reported that 91 percent of the seniors who had graduated from Harvard University the previous June had received honors, prompting an investigation that concluded grade inflation was indeed a serious problem at Harvard.

Faculty members have not fulfilled the responsibilities associated with their proclaimed right to be the final judges of student performance. In shirking that duty, they have also neglected their broader obligations to society: Teachers weaken rather than bolster the commonweal when they fail to award meaningful grades. Grading laxness at all levels of American education has contributed directly or indirectly to a variety of problems, including declining scores on the SAT, decreases in the ability of American undergraduate and graduate students to understand prose, and poor training in mathematics and science, which puts American students behind their peers in many European and Asian countries.

Could more-realistic grading stem the tide? Ample evidence shows that students learn more when the bar for success is raised rather than lowered. For example, Valen Johnson's Grade Inflation contains analyses demonstrating that students who took prerequisite courses from teachers who were tough graders performed better in upper-division classes than did students whose prerequisite courses were taught by easier graders.

What are universities doing?

Carpe diem.A few universities have established grading standards, and their administrators monitor professors' compliance. Perhaps the most heralded example is Princeton University's adoption of limits on the percentage of A's given in undergraduate courses. And in the M.B.A. programs at the University of Chicago and New York University's Leonard N. Stern School of Business, online grade-reporting systems will not accept an instructor's grades in certain courses if the grades exceed school or departmental standards.

3 Comments:

I am curious how Princeton can limit an "A" grade without using a curve. And, curves do not evaluate student outcomes—the currently accepted grading criterion.

Having taught at two different colleges where the average grade I gave at one college was a "C" and the average grade at the other college was an "A" for the same material, I found the students in the class made the difference.

The "A" class was made up of General Motors' apprentices who had been through a rigorous selection process and skimmed from the top of a list. The "C" students were from an open-door- policy college who were tracked from high school to trade school. Same material, highly different outcomes, so accordingly highly different grades.

It would seem like prestigious colleges such as Harvard and Yale would contain highly motivated and driven students who are at the top of their class. I would be somewhat surprised if most of the students did not receive "A"s and graduate with honors.

There probably is a problem with grade inflation, but using Princeton and Yale, in my opinion, does not bolster that argument. My dean pressured me to raise the grades of a few complaining students, but I was able to resist because I was not dependent on that job for my livelihood and did not feel too intimidated. It was still unpleasant being called into his office and having my performance questioned for just doing my job.

I agree that setting the expectation bar high motivates the students who want to learn and weeds out those who do not. Lowering the bar and watering down a class does not benefit anyone.

According to the evidence presented, schools as a whole have had their average grade increase a few tenths of a point over 15 years. Clearly a national crisis.

(In point of fact, what do 100 year trends look like? Is the recent increase even statistically significant? I would expect a lot better evidence from someone holding themselves up as a critic of professional educators.)

"Faculty members have not fulfilled the responsibilities associated with their proclaimed right to be the final judges of student performance." As a Faculty member, I have never proclaimed such a right. I would far prefer an independent judgement of my students' abilities / performance / whatever the heck it is grades are supposed to measure. But society is too cheap and lazy to go there, so I do what I can.

"In shirking that duty, they have also neglected their broader obligations to society: Teachers weaken rather than bolster the commonweal when they fail to award meaningful grades." Frankly, under the current system someone else can "bolster the commonweal" (are you joking?). If you want me to teach and research, I'm really happy to do that. If you want me to play "education policeman", you first have some responsibilities to me.

(1) Tell me exactly what the grades I'm giving out are supposed to measure. There's lots of choices here: ability to recall information on the subject (immediately and in the distant future), ability to apply the learnings of the subject, effort put into the course, improvement during the course, etc, etc.

(2) Tell me how a student's performance on these measures is supposed to translate into a grade. You only give me one "number" (not even that—you give me a few choices of letter). Should the grade reflect the relative class ranking of the student, the general ranking of the student across some hypothetical population, an absolute value indicating achievement?

(3) Don't discourage low grades. I've never had an instant's grief from anyone over giving a "too high" grade. When I've given grades that a student or supervisor have thought "too low", I've been threatened with lawsuits, had grades changed over my objections, and received poor performance reviews. The message is clear.

"Grading laxness at all levels of American education has contributed directly or indirectly to a variety of problems, including declining scores on the SAT, decreases in the ability of American undergraduate and graduate students to understand prose, and poor training in mathematics and science, which puts American students behind their peers in many European and Asian countries." The evidence provided for these claims is quite weak. I suppose it's hard to argue with "has contributed directly or indirectly to". I greatly doubt that the contribution is particularly strong, or particularly direct; anyone involved in University education can list many co-factors that are much bigger contributors.

I'm Faculty. I'm paid literally less than half what I would make to do similar work in industry. I lack basic necessities of equipment and support needed to teach my discipline. I have a huge variety of tasks besides teaching piled on me—most notably, the obligation to be a world-class researcher. In spite of all these handicaps, I win awards for my teaching and work with students.

Don't you dare put our country's educational problems on my course grading.

The way the limited number of A grades system works is quite simple but not as effective as it sounds. The BBA program at my school has this type of system. However, the system ONLY limits the percentage of A grades, it does not say anything about the rest of the grades in the class, meaning that in most cases the grades are distributed between A and C, with only severe outliers getting a C- or lower. I think this is hardly an effective solution.

Post a Comment

<< Home